My son is learning how to build a website - if you want to check out his work, take a look at:

http://www.planetnana.co.il/yehoshua1997/

It's still very much a work in progress, but be sure to check back soon.

If you want to write to him, his email is: yehoshuasedley -at- hotmail.com

Monday, December 24, 2007

Sunday, December 23, 2007

Neturei Karta in Iran

For those (including my brother) who were worried about Neturei Karta and their support of Iran were probably relieved to finish Messechet Ketuvot and find sources for Neturei karta, after all - doesn't דף ק"י-קי"א say:

דאמר רב יהודה כל העולה מבבל לארץ ישראל עובר בעשה שנאמר (ירמיהו כז) בבלה יובאו ושמה יהיו עד יום פקדי אותם נאם ה'

Rav Yehuda Says: Anyone who goes from Bavel to Eretz Yisrael transgresses an Aseh - "They will be brought to Bavel, and there they will be until I redeem them".

You see - by going to Iran instead of Eretz Yisrael, Neturei Karta were just showing that they posken by Rav Yehuda.

I fee MUCH happier now :)

דאמר רב יהודה כל העולה מבבל לארץ ישראל עובר בעשה שנאמר (ירמיהו כז) בבלה יובאו ושמה יהיו עד יום פקדי אותם נאם ה'

Rav Yehuda Says: Anyone who goes from Bavel to Eretz Yisrael transgresses an Aseh - "They will be brought to Bavel, and there they will be until I redeem them".

You see - by going to Iran instead of Eretz Yisrael, Neturei Karta were just showing that they posken by Rav Yehuda.

I fee MUCH happier now :)

Thursday, December 20, 2007

Funding the Palestinians

Well, so far I haven't entered into the world of Politics - although I may do that more in the future, however I just saw this interesting article that I thought I should link to.

There is a common mis-conception that Poverty is directly related to terrorism - i.e., the poorer an individual or society is, the more likely that they will use terror or violence, after all - what have they got to loose?

This is possibly the motivation of the EU and the rest of the International community to pledge millions of dollars (Euros?) into the Palestinian Authority.

The reality is exactly the opposite; when an individual or society is very poor, they are worried about putting food on the table and a roof over their head. It is only once the have less financial worries that they start to worry about politics, or radical politics that leads to terrorism.

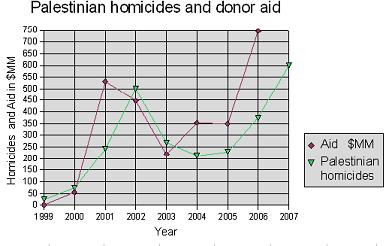

I just saw an interesting article that backed this up, look at the following tables (taken from www.camera.org )

The Red line shows aid given to the Palestinians, the Green Line shows the number of Palestinian Homicides.

Seems like there is a pretty strong relationship...

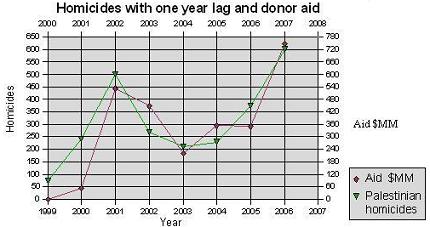

If you adjust the Green Line by a year, it seems to indicate that there as almost 1:1 relationship between money to the PA and terrorism within a year.

Makes you wonder why the Europeans are so keen to give Abbas money.

Any thoughts?

There is a common mis-conception that Poverty is directly related to terrorism - i.e., the poorer an individual or society is, the more likely that they will use terror or violence, after all - what have they got to loose?

This is possibly the motivation of the EU and the rest of the International community to pledge millions of dollars (Euros?) into the Palestinian Authority.

The reality is exactly the opposite; when an individual or society is very poor, they are worried about putting food on the table and a roof over their head. It is only once the have less financial worries that they start to worry about politics, or radical politics that leads to terrorism.

I just saw an interesting article that backed this up, look at the following tables (taken from www.camera.org )

The Red line shows aid given to the Palestinians, the Green Line shows the number of Palestinian Homicides.

Seems like there is a pretty strong relationship...

If you adjust the Green Line by a year, it seems to indicate that there as almost 1:1 relationship between money to the PA and terrorism within a year.

Makes you wonder why the Europeans are so keen to give Abbas money.

Any thoughts?

Tuesday, November 6, 2007

Memories

I still have a lot of memories and thoughts about the trip to Budapest to write up - I haven't forgotten, I just have been very busy at work lately.

In the mean time, I wanted to share this video that I just saw:

בלי נדר I'll write up about the amazing food ee ate and things we saw in Budapest in the next few days.

In the mean time, I wanted to share this video that I just saw:

בלי נדר I'll write up about the amazing food ee ate and things we saw in Budapest in the next few days.

Labels:

Jewish Music

Friday, October 26, 2007

Education - ושננתם לבניך

We Stayed in an apartment that we rented on Veres Pálné utca. The street was named after the woman who established the first woman's Gimnázium (Academic High School) in Budapest. Her statue adorns the end of the street, a few doors from where we stayed.

The school established by Mrs Veres changed the life of my Grandmother who was among the first Hungarian women to attend high school. Her older sister Ella never went to a Gimnázium, but by the time her younger sister Mårta was high-school age, secondary school education for women was very common.

After settling into the apartment where we were staying, we walked around the area. Dad showed us the Presbyterian school that he attended for 2 years (he switched to the Jewish school when his younger brother Janos was denied entry to the school as they had a quota for non-Presbyterian students).

My father attended this school as it was very close to their home, and it was the school that his grandfather had attended.

We also saw the house where my father's grandparents lived. After the war the house was divided (due to the housing shortage) and my aunt Mårta lived in the other hlaf with her husband Ivan. They stayed there until their death in the 1990s. We also saw the apartment my father lived in before the war (including the window he fell out of as a toddler, he still has the scar on his neck from that almost fatal accident).

Renting a regular apartment in that part of town gave me us a small appreciation of what life may have been like - the style of building apartments with very high ceilings built around a common courtyard (with a tap, which at one time may have been the only working tap in the building).

After walking around that part of Pest for a few hours, we headed to the Jewish Quarter for dinner - but that will have to be my next post.

Labels:

Budapest

Thursday, October 25, 2007

Budapest - טיול שורשים

Well, I just got back from an amazing three day tiyul with my father and siblings in Budapest - the city my father was born, went to school (until age 15), survived the Holocaust, and most importantly the city where our family's roots are firmly buried.

It was a real insight into the world where my father grew up and helped me to understand where our family comes from.

There is so much to write about it's hard to know where to start, but over the next few days I'll try to write down thoughts and memories, and hopefully will be able to make a coherent retelling of a truly amazing three days.

It was a real insight into the world where my father grew up and helped me to understand where our family comes from.

There is so much to write about it's hard to know where to start, but over the next few days I'll try to write down thoughts and memories, and hopefully will be able to make a coherent retelling of a truly amazing three days.

Labels:

Budapest

Saturday, September 15, 2007

Shana Tova

Well, we just had a wonderful Chag in Buchman Darom.

I wasn't sure where I was going to daven over Rosh HaShana - I had narrowed it down to three options:

I had planned to go to Buchman Darom the following morning, but overslept (they started at 6:30, Lev Achim at 8:00), so I went to Lev Achim, and was again disappointed - a lot of noise, not much singing, and when they tried to sing different parts of the room were singing different tunes.

Second day I made it up to the Buchaman Darom minyan, there were about 40 people there, in someones living room, and I think that it was the best Rosh HaShana davening that I've ever experienced, certainly the best since I left Yeshiva (even though merkaz Modi'in where I davened the last few years was also outstanding).

It was a very "Gush" minyan", and I'm now certainly keen to join the Amuta, and hopefully this wondering homeless minyan will find a permanent, or at least temporary location soon.

It is still not known where they will daven Yom Kippur, but I hope that it'll be better than a street corner as my parents will be with us.

I didn't make it to the Hesder Yeshiva, but was there for slichot erev Rosh HaShana, and IY"H will be back again for slichot tomorrow morning.

One more point about Rosh HaShana - As always, Rabbi Lau's Shabbat Shuva Drosha was outstanding. It's amazing how many people they can pack into the Merkaz Modi'in shul (more of an unfinished basement than a shul),.

I wasn't sure where I was going to daven over Rosh HaShana - I had narrowed it down to three options:

- Minyan Lev Achim, which davens in the Beit Midrash of the Bnei Akiva Yeshiva (about 8 minutes walk from our home)

- Hesder Yeshiva, which has its Beit Midrsah downstairs in the Bnei Akiva Yeshiva

- The un-nammed Buchman Darom minyan, which moves from place to place, but davened both mornings of Rosh HaShana in a private home, and in the evenings on a street corner.

I had planned to go to Buchman Darom the following morning, but overslept (they started at 6:30, Lev Achim at 8:00), so I went to Lev Achim, and was again disappointed - a lot of noise, not much singing, and when they tried to sing different parts of the room were singing different tunes.

Second day I made it up to the Buchaman Darom minyan, there were about 40 people there, in someones living room, and I think that it was the best Rosh HaShana davening that I've ever experienced, certainly the best since I left Yeshiva (even though merkaz Modi'in where I davened the last few years was also outstanding).

It was a very "Gush" minyan", and I'm now certainly keen to join the Amuta, and hopefully this wondering homeless minyan will find a permanent, or at least temporary location soon.

It is still not known where they will daven Yom Kippur, but I hope that it'll be better than a street corner as my parents will be with us.

I didn't make it to the Hesder Yeshiva, but was there for slichot erev Rosh HaShana, and IY"H will be back again for slichot tomorrow morning.

One more point about Rosh HaShana - As always, Rabbi Lau's Shabbat Shuva Drosha was outstanding. It's amazing how many people they can pack into the Merkaz Modi'in shul (more of an unfinished basement than a shul),.

Tuesday, September 4, 2007

Home Sweet Home

Well, we're back home in Modi'in, I haven't had time (or energy) to blog since we got back, but I thought that I could share a few thoughts. Hopefully later in the week I'll be back in a regular blogging routine.

The House - we are delighted with our new house, our immediate neighbors seem nice, and a nice mix of native Israelis, Olim, Dati'im, and not-yet dati'im.

The Neighborhood - we have many friends who moved into Buchman Darom over the past few months, and everyone seems happy with the decision to move here. A large percentage of the neighborhood is religious, and there is quite a high percent of English Speakers (ohh no - please don't tell me that I ended up in Ramat Beit Shemesh or Efrat)

Shuls - well, there aren't ANY - not a single shul in Buchman Darom. There are several minyanim in peoples homes on Shabbat (especially Erev Shabbat), and the Yeshiva in Buchman Tzafon is only a few minutes walk from my house, they seem to have nice Shabbat and weekday minyanim - looks like we'll be there for the Chagim.

Schools - all four kids are in different schools, three of them are in new schools and so far everyone seems happy, although I'm sure that I'll have more to write on this topic in the future

Heat - it's HOT, could someone please turn down the heat outside! We still don't have air-conditioning!

Routine - this week, with everyone back in school we have started to get the family back into a routine, makes life easier for everyone

I've got a lot more to say on all of the above, as well as some thoughts on the Parsha, and Daf Yomi - but I've gotta get a document finished for work.

The House - we are delighted with our new house, our immediate neighbors seem nice, and a nice mix of native Israelis, Olim, Dati'im, and not-yet dati'im.

The Neighborhood - we have many friends who moved into Buchman Darom over the past few months, and everyone seems happy with the decision to move here. A large percentage of the neighborhood is religious, and there is quite a high percent of English Speakers (ohh no - please don't tell me that I ended up in Ramat Beit Shemesh or Efrat)

Shuls - well, there aren't ANY - not a single shul in Buchman Darom. There are several minyanim in peoples homes on Shabbat (especially Erev Shabbat), and the Yeshiva in Buchman Tzafon is only a few minutes walk from my house, they seem to have nice Shabbat and weekday minyanim - looks like we'll be there for the Chagim.

Schools - all four kids are in different schools, three of them are in new schools and so far everyone seems happy, although I'm sure that I'll have more to write on this topic in the future

Heat - it's HOT, could someone please turn down the heat outside! We still don't have air-conditioning!

Routine - this week, with everyone back in school we have started to get the family back into a routine, makes life easier for everyone

I've got a lot more to say on all of the above, as well as some thoughts on the Parsha, and Daf Yomi - but I've gotta get a document finished for work.

Monday, August 27, 2007

Daf Yomi and the Titanic

I'm back in Modi'in now and there are a million things that I want to write about - Shabbat in Buchman Darom, the choice of minyanim here, my new neighbours, kids and jetlag, the new school year - and hopefully, when I have time I'll talk about all of the above.

Right now I'm frantically trying to catch up on work, so all I'll add is a quick link related to yesterday's daf.

Yesterday we covered the status of a woman who's husband was lost at sea. One of the most famous cases was of course the Psak of Rav Yaakov Misken who ruled for the wife of Shminon Meizner who was on the Titanic.

I searched the Web for a copy of the Psak, and finally found it using the way back machine and looking at the archives of HebrewBooks.com.

You can view a copy of the Psak here.

Stay tuned for Modi'in-related stuff

Right now I'm frantically trying to catch up on work, so all I'll add is a quick link related to yesterday's daf.

Yesterday we covered the status of a woman who's husband was lost at sea. One of the most famous cases was of course the Psak of Rav Yaakov Misken who ruled for the wife of Shminon Meizner who was on the Titanic.

I searched the Web for a copy of the Psak, and finally found it using the way back machine and looking at the archives of HebrewBooks.com.

You can view a copy of the Psak here.

Stay tuned for Modi'in-related stuff

Labels:

Daf Yomi

Friday, August 17, 2007

Ottawa

Well, we just had a lovely three days in Ottawa with three of the kids (Yael stayed back with her Saba and Savta).

A few highlights:

On Sunday we visited Upper Canada Village, a recreation of a Canadian Village from the 1860s. The kids had a great time visiting the various buildings and speaking to people from that period.

If you have a chance to go, allow extra time in the Schoolhouse, which this kids enjoyed the most.

Monday morning we took the kids to the Museum of Civilization which not only has an IMAX (we saw an amazing movie about the Alps), and a very well done history of Canada, but they have an excellent and educational kids museum which kept the kids entertained for hours.

In the afternoon we took them on a river ride which was, well, a boat ride on a river (go figure) .

Sunday night I took Yehoshua to the Sound and Light Show outside Parliament which I'd also recommend if you find yourself in Ottawa on a Summer evening.

On the way back to Toronto on Tuesday we stopped at Sanders farm which has 10 mazes, all with an educational theme, as well as a wagon ride and other activities - again I'd highly recommend it if you're looking for a full day's entertainment for your kids in the Ottawa region.

While in Ottawa I davened at the Young Israel of Ottawa. Interesting to see that the minyan is being taken over by Chabad - at least half the minyan were chabadnikim, and you can see that they are slowly trying to insert Chabad minhagim into the shul - but I guess that's a topic for another Post - or maybe not (don't get me started on Chabad, I may say something that I'll regret later)

A few highlights:

On Sunday we visited Upper Canada Village, a recreation of a Canadian Village from the 1860s. The kids had a great time visiting the various buildings and speaking to people from that period.

If you have a chance to go, allow extra time in the Schoolhouse, which this kids enjoyed the most.

Monday morning we took the kids to the Museum of Civilization which not only has an IMAX (we saw an amazing movie about the Alps), and a very well done history of Canada, but they have an excellent and educational kids museum which kept the kids entertained for hours.

In the afternoon we took them on a river ride which was, well, a boat ride on a river (go figure) .

Sunday night I took Yehoshua to the Sound and Light Show outside Parliament which I'd also recommend if you find yourself in Ottawa on a Summer evening.

On the way back to Toronto on Tuesday we stopped at Sanders farm which has 10 mazes, all with an educational theme, as well as a wagon ride and other activities - again I'd highly recommend it if you're looking for a full day's entertainment for your kids in the Ottawa region.

While in Ottawa I davened at the Young Israel of Ottawa. Interesting to see that the minyan is being taken over by Chabad - at least half the minyan were chabadnikim, and you can see that they are slowly trying to insert Chabad minhagim into the shul - but I guess that's a topic for another Post - or maybe not (don't get me started on Chabad, I may say something that I'll regret later)

Thursday, August 16, 2007

Eyes down, heart up

Last night I went with my wife to see Kooza, a circus-production currently playing in toronto (we head home to Modi'in next week)

One of the acts was a group of three performers who managed to position their bodies in very unnatural shapes - I now realize that they were just a day ahead ini Daf Yomi and were trying to follow Rabbi Yeshmael's advice in today's daf:

Rebbi Yishmael b'Rebbi Yosi explains .... when one

prays, he should direct his eyes downward, in the direction of the dwelling

place of the Shechinah in Eretz Yisrael, and he should direct his heart upward

towards heaven.

Well, here are some pictures of the performers last night trying to keep their eyes facing down and heart facing up.....

Sunday, August 12, 2007

Blast From The Past

Well, I'm still in Totonto - we head back home to Modi'in in just over a week.

Friday night I was in my Father-in-law's shul, and at the back of the shul I saw a familiar face that I hadn't seen for 20 years. Rabbi Moshe Berlove who was the Rabbi in Wellington while I was a teenager there was in town for a family Wedding.

I had a wonderful opportuniy to catch up with him after davening, and also spoke for a while with his son Melech who was all of five years old last time a I saw him.

I was very close to Rabbi Berlove 20 years ago and spent many many Shabbatot at their home, but I haven't been in contact with them since he left New Zealand in 1989. It was lovely to catch up and share memories. He shared with me a story about my Grandmother that I didn't know before and we talked about various things that he remembered from his time in Wellington.

Tomorrow I'm off to Ottawa with my family, and probably wont have acgnace to Blog until I get back on Ruesday night.

Maybe when I get back I'll write some reactions to the article that was in Friday's In Jerusalem about Modi'in.

Friday night I was in my Father-in-law's shul, and at the back of the shul I saw a familiar face that I hadn't seen for 20 years. Rabbi Moshe Berlove who was the Rabbi in Wellington while I was a teenager there was in town for a family Wedding.

I had a wonderful opportuniy to catch up with him after davening, and also spoke for a while with his son Melech who was all of five years old last time a I saw him.

I was very close to Rabbi Berlove 20 years ago and spent many many Shabbatot at their home, but I haven't been in contact with them since he left New Zealand in 1989. It was lovely to catch up and share memories. He shared with me a story about my Grandmother that I didn't know before and we talked about various things that he remembered from his time in Wellington.

Tomorrow I'm off to Ottawa with my family, and probably wont have acgnace to Blog until I get back on Ruesday night.

Maybe when I get back I'll write some reactions to the article that was in Friday's In Jerusalem about Modi'in.

Friday, August 10, 2007

Parshat Raeh

I am really busy at work right now, and don't have time to write a proper post, but there is a Rashi at the end of Shlishi of this week's Parsha that is bothering me, and I wanted to write it down.

If anyone has any thoughts on this Rashi, Please leave me a comment.

Pasuk 12:28 says:

כח שְׁמֹר וְשָׁמַעְתָּ, אֵת כָּל-הַדְּבָרִים הָאֵלֶּה, אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי, מְצַוֶּךָּ: לְמַעַן יִיטַב לְךָ וּלְבָנֶיךָ אַחֲרֶיךָ, עַד-עוֹלָם--כִּי תַעֲשֶׂה הַטּוֹב וְהַיָּשָׁר, בְּעֵינֵי יְהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ.

Guard and listen to all these things that I command you so that it should be good for you and your children after you for ever, for you should do the good and the straight in the eyes of HaShem your G-d

(my translation).

Rashi says:

"Hatov" (good), means in the eyes of Heaven

"Hayashar" (straight) means in the eyes of people

Leaving aside questions of reward and punishment (which the pasuk relates to directly), my question is why is it important that our actions are not only Right (in the eyes of Heaven), but that they are seen to be right.

Surely there are cases where the right thing to do will be critisized or rejceted by society.

If an action is Right, but not embraced by society - does that make it any less right?

I wanted to follow this up in other sources, but I am travelling right now and don't have easy access to sforim.

If anyone has any insights, please leave me a comment.

Shabbat Shalom

If anyone has any thoughts on this Rashi, Please leave me a comment.

Pasuk 12:28 says:

כח שְׁמֹר וְשָׁמַעְתָּ, אֵת כָּל-הַדְּבָרִים הָאֵלֶּה, אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי, מְצַוֶּךָּ: לְמַעַן יִיטַב לְךָ וּלְבָנֶיךָ אַחֲרֶיךָ, עַד-עוֹלָם--כִּי תַעֲשֶׂה הַטּוֹב וְהַיָּשָׁר, בְּעֵינֵי יְהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ.

Guard and listen to all these things that I command you so that it should be good for you and your children after you for ever, for you should do the good and the straight in the eyes of HaShem your G-d

(my translation).

Rashi says:

"Hatov" (good), means in the eyes of Heaven

"Hayashar" (straight) means in the eyes of people

Leaving aside questions of reward and punishment (which the pasuk relates to directly), my question is why is it important that our actions are not only Right (in the eyes of Heaven), but that they are seen to be right.

Surely there are cases where the right thing to do will be critisized or rejceted by society.

If an action is Right, but not embraced by society - does that make it any less right?

I wanted to follow this up in other sources, but I am travelling right now and don't have easy access to sforim.

If anyone has any insights, please leave me a comment.

Shabbat Shalom

Labels:

Parsha

Thursday, August 9, 2007

Daf Yomi - Yevamot 97B - Riddles

I had a lot of trouble getting my head around the "riddles" in today's daf.

These riddles describe a variety of seemingly impossible relationships.

Anyway, I thought that if I tried to draw them on a diagram I might get a clearer understanding.

Please let me know if you think that I got these diagrams correct. If anyone wants a printed copy, I'd be happy to send them as a PDF.

The translation I'm using comes from Kollel Iyun Hadaf. In each of the diagrams, the woman in green is speaking to the man in red.

These riddles describe a variety of seemingly impossible relationships.

Anyway, I thought that if I tried to draw them on a diagram I might get a clearer understanding.

Please let me know if you think that I got these diagrams correct. If anyone wants a printed copy, I'd be happy to send them as a PDF.

The translation I'm using comes from Kollel Iyun Hadaf. In each of the diagrams, the woman in green is speaking to the man in red.

Riddle #1:

'He is a paternal, but not a maternal, brother, and he is my mother's husband, and I am the daughter of his wife.' (How can this arise?)

Answer (Rami bar Chama):

This is unlike R.

Yehudah (who forbids a man to marry a woman his father raped. The girl speaking

was born out of wedlock; her paternal brother married her mother).

Riddle #2:

'He is my brother, and my son; I am the sister of the one I carry on my shoulder'.

Answer:

The case is, a Nochri had Bi'ah with his daughter. (We prefer not to say that a Yisrael did so.)

Riddle #3:

'Shalom to you, my son; I am the daughter of your sister'.

Answer:

The case is, a Nochri had Bi'ah with his daughter's daughter.

Riddle #4 (asked to water carriers):

'The one I carry is my son, and I am the daughter of his brother.'

Answer:

The case is, a Nochri had Bi'ah with his son's daughter.

Riddle #5:

'Alas, my brother is my father, my husband, the son of my husband and the husband of my mother, and I am the daughter of his wife, and he does not give bread to his brethren, the orphaned children of his daughter.

Answer:

The case is, a Nochri Ploni fathered a girl Plonis through his mother, and later fathered children from Plonis, and Ploni's father Almoni fathered children through Plonis. (Ploni married Plonis, who is his daughter and sister. Almoni died, and Ploni refused to feed Almoni's children through Plonis, who are Ploni's grandchildren and also his brothers.)

Riddle #6:

'I and you are brothers; I and your father are brothers; I and your mother are brothers.

Answer:

The case is, a Nochri fathered two girls from his mother, and then fathered a son from one of his daughters. The son's mother's sister says the above to him.

Riddle #7:

I and you are the children of sisters, I and your father are the children of brothers, and I and your mother are the children of brothers. This indeed is possible also in the case of a permissible marriage.

Note: The translation of this Riddle from Shema Yisrael didn't seem right, the translation I'm using here is from Daf Notes.

Answer:

This can arise in a permitted way! Reuven, Shimon and Levi are brothers. Reuven has two daughters; Shimon married one of them and Levi's son married the other. Shimon's son says thusly to the son of Levi's son.

Labels:

Daf Yomi

Tuesday, July 31, 2007

Daf Yomi: Get Al T’nai

The perek we started this week in daf Yomi discusses the tragic case of a woman whose husband goes missing. In what circumstances may she remarry? What happens if she remarries and then her first husband turns up alive? What is the status of the kids in such a circumstance?

Unfortunately, this is a very real halachic problem and one that is all to common.

Questions about missing husbands arose as a result of 9/11 when many many people were murdered while at work in the World Trade Center.

There are also the tragic cases of Tami Arad, and more recently Karnit Goldwasser, whose husbands (Ron and Udi) have been missing in action for many years (Ron Arad for over 20 years, Udi Goldwasser for over a year, may HaShem please bring them and the other MIAs home back to the families quickly and in good health).

There were also many questions by women who returned from the Ashes of Europe 60 years ago whose husband’s disappeared and whose fate was not known.

I once read (and I’m sorry I don’t remember where) that a way to view Jewish History, and assess the important issues of each generation is to look at the Shutim that were being asked or addressed by the G’dolim of that generation. If you look at Shutim in the second half of the Twentieth Century, particularly at Shutim by Rav Moshe Feinstein and Rav Shlomo Goren, you’ll see that the tragedy of Agunot is an issue which continues to trouble our nation well into the modern era.

One of the questions that came up in the Daf Yomi Shiur was why we don’t reinstate the Get al T’nai that David HaMelech had his soldiers sign before they went out to battle.

A get Al T’nai (as far as I understand) is basically a document that says that if a soldier does not return within a fixed period of time, this is to be considered a get retroactively, and the wife has the status of a divorcee and not an Aguna.

Had such a practice been in place in the IDF, this would have helped the plight of Tami and Kamit, not to mention the wives of the soldiers lost on the Dakar submarine, and many other cases of soldiers whose fate is unknown.

I vaguely remembered hearing that in the early days of the State there was a discussion about instituting a Get al T’nai, and with a little Internet research I found a reference to Meshiv Milchama, a book of Halachot for soldiers by Rav Goren where he discusses a proposal from Chief Rabbi Herzog to institute such a Get for all soldiers. Rabbi Goren actually drafted a Get al T’nai, but dropped the idea when commanders said that this proposal would be demoralizing for soldiers. I briefly looked for a copy of the book in the B’nai Torah Library, but didn’t find it.

It’d be interesting to read this source if/when I manage to locate a copy.

What surprised me more in my Internet search is that although it is not standard practice in the IDF today, there are many other modern examples of use of a Get Al T’nai.

The person sitting next to me at Daf Yomi on Sunday said that he actually had a Get Al T’nai that his wife’s grandfather wrote to his wife when he went to battle in World War 1.

According to the Jewish Virtual Library this get was used during the Russio-japanese war:

I also found this short description that claims that a Get Al T’nai is also used today in the IDF in certain cases, although I was unaware of this, and am not sure of the accuracy:

The above was certainly news to me, I had always thought that the concept of "get Al T'nai" had not been used since King David's army - I guess that you learn something every day.

Unfortunately, this is a very real halachic problem and one that is all to common.

Questions about missing husbands arose as a result of 9/11 when many many people were murdered while at work in the World Trade Center.

There are also the tragic cases of Tami Arad, and more recently Karnit Goldwasser, whose husbands (Ron and Udi) have been missing in action for many years (Ron Arad for over 20 years, Udi Goldwasser for over a year, may HaShem please bring them and the other MIAs home back to the families quickly and in good health).

There were also many questions by women who returned from the Ashes of Europe 60 years ago whose husband’s disappeared and whose fate was not known.

I once read (and I’m sorry I don’t remember where) that a way to view Jewish History, and assess the important issues of each generation is to look at the Shutim that were being asked or addressed by the G’dolim of that generation. If you look at Shutim in the second half of the Twentieth Century, particularly at Shutim by Rav Moshe Feinstein and Rav Shlomo Goren, you’ll see that the tragedy of Agunot is an issue which continues to trouble our nation well into the modern era.

One of the questions that came up in the Daf Yomi Shiur was why we don’t reinstate the Get al T’nai that David HaMelech had his soldiers sign before they went out to battle.

A get Al T’nai (as far as I understand) is basically a document that says that if a soldier does not return within a fixed period of time, this is to be considered a get retroactively, and the wife has the status of a divorcee and not an Aguna.

Had such a practice been in place in the IDF, this would have helped the plight of Tami and Kamit, not to mention the wives of the soldiers lost on the Dakar submarine, and many other cases of soldiers whose fate is unknown.

I vaguely remembered hearing that in the early days of the State there was a discussion about instituting a Get al T’nai, and with a little Internet research I found a reference to Meshiv Milchama, a book of Halachot for soldiers by Rav Goren where he discusses a proposal from Chief Rabbi Herzog to institute such a Get for all soldiers. Rabbi Goren actually drafted a Get al T’nai, but dropped the idea when commanders said that this proposal would be demoralizing for soldiers. I briefly looked for a copy of the book in the B’nai Torah Library, but didn’t find it.

It’d be interesting to read this source if/when I manage to locate a copy.

What surprised me more in my Internet search is that although it is not standard practice in the IDF today, there are many other modern examples of use of a Get Al T’nai.

The person sitting next to me at Daf Yomi on Sunday said that he actually had a Get Al T’nai that his wife’s grandfather wrote to his wife when he went to battle in World War 1.

According to the Jewish Virtual Library this get was used during the Russio-japanese war:

During the Russo-Japanese war of 1905, some great Russian rabbis visited the troops before they left for the front and persuaded the Jewish soldiers to issue a get al tenai, a "conditional divorce," so as to free their wives from the status of agunah should the men fail to return. But obviously this temporary procedure, however helpful in individual cases, did not meet the growing dimensions of the problem.

I also found this short description that claims that a Get Al T’nai is also used today in the IDF in certain cases, although I was unaware of this, and am not sure of the accuracy:

Conditional get

As there is conditional marriage, there is also an option of conditional divorce. According to Mishnah Gittin a man can give his wife a get and tell her that it would be valid in case of an adverse event such as: not returning from a trip, being declared missing in action during a war, loosing his mind and other exceptional cases. A different option is for a representative of the husband to write his wife a get if such an event occurs. At times, the rabbis took such initiative and suggested that a conditional get be written. In 1987 Israel extradited a Jew named William Nakash to France. Before he left the country, the Rabbinic Court in Jerusalem insisted that he deposit a conditional get with the court, which Nakash agreed to.

This solution, however, was only suggested in relation to soldiers going off to war. According to Halakhah, it is not possible to give a conditional get once and to keep it until it is needed. If a man goes to war, gives his wife a conditional get, then comes home on vacation and is intimate with her before returning to war, he must give her a new get. This means that a new conditional get must be deposited each time. The IDF (Israeli Defense Forces) has a conditional get version that can be deposited before a particularly dangerous mission.

The above was certainly news to me, I had always thought that the concept of "get Al T'nai" had not been used since King David's army - I guess that you learn something every day.

Labels:

Daf Yomi

Tu B’Av and a tribute to a true Eshet Chayil

I was planning to write a shot piece on the Daf, or specifically the terrible plight of Agunot which is discussed in the perek that we just started (more specifically, the terrible situation that arrises when a husband disappears and his wife has reason to believe that he is dead) – however, I thought that I should start off with a few words about TU B’Av, and now that I started writing, it seems that I should stick with Tu B’Av, and leave the Daf for a different day (stay tuned....)

Today is Tu B'av

The Mishna (תענית ד,א) states that there were no happier days for Yisrael than the Fifteenth of Av and Yom Kippur, and indeed today is a very happy day, not only did we skip Tachanun in shul this morning (on a Monday no-less), but today is the anniversary of the date that Debbie and I got engaged.

Today, 12 years ago I proposed to Debbie in Niagara Falls. I don’t think that there could have been a more romantic date or location to get engaged.

After twelve wonderful years since our engagement (and our wedding a few months later), I suppose that this blog is a great opportunity for me to look back on how fortunate I am to have found an Eishet Chayal as wonderful and caring as Debbie.

A few thoughts about Debbie:

Today is Tu B'av

The Mishna (תענית ד,א) states that there were no happier days for Yisrael than the Fifteenth of Av and Yom Kippur, and indeed today is a very happy day, not only did we skip Tachanun in shul this morning (on a Monday no-less), but today is the anniversary of the date that Debbie and I got engaged.

Today, 12 years ago I proposed to Debbie in Niagara Falls. I don’t think that there could have been a more romantic date or location to get engaged.

After twelve wonderful years since our engagement (and our wedding a few months later), I suppose that this blog is a great opportunity for me to look back on how fortunate I am to have found an Eishet Chayal as wonderful and caring as Debbie.

A few thoughts about Debbie:

- Debbie is a wonderful, supporting wife. Over the past twelve years, as I’ve grown spiritually, professionally, and personally, I have always felt that I have someone to grow with. Debbie is a partner in life that I’ve always felt comfortable talking with and sharing concerns with.

- Debbie is a wonderful mother. She showers love and concern over all four of our kids, guiding them and helping them to grow and develop into fine young people. I’m not sure whether our kids realize how lucky they are to have a mother like Debbie, but I am sure as they grow up they will continue to be fine Jews as a result of the love and guidance that they receive from their mother.

- Debbie is a realistic and practical person. We are currently moving into a new house, the first house that we owned. It was Debbie who took the time to research locations and contractors, who took an active role in every part of the construction of the house, from the kitchen layout, to the position of every electrical socket.

Please G-d, Debbie and I will enjoy many many years together in this house of our dreams. - Professionally Debbie is also an outstanding teacher. In the few years that we have been in Modi’in, she has already established a reputation as a highly sought-after English teacher. She is full of creative ideas, and takes a strong interest in the development of her students. Just as our kids are lucky to have you as a mother, your students are lucky to have you as a teacher.

I feel very fortunate to have found a life partner as wonderful as Debbie.

Debbie, thank you for being you. It's been a wonderful 12 years together, and Please G-d we will continue to grow and develop together for many many years to come.

Friday, July 27, 2007

Parshat V'Etchanan

I’m kinda busy at work today, and as a Friday it’s a short day (I’m in Toronto right now which is why I’m working on a Friday at all), but I thought that I couldn’t let my first Shabbat come and go without at least a few thoughts on the Parsha.

As I mentioned, I’m in Toronto right now, and on Shabbat we’re planning on walking up to Ayin Letzion, which is a minyan that I was involved with while we were on shlichut here. It is possible that the Rabbi there will ask me to say a few words at Sudat Shlishit, it’s also not impossible that I’ll have the opportunity to say something at the Shabbat table, so I’d better come up with a few coherent thoughts, just in case.

Parshat Va’etchanan is jam-packed with concepts, both big and small. It’s almost like a “Greatest hits” parsha - 10 commandments and Shema Yisrael are two biggies that spring to mind, but there are plenty of other meaningful goodies.

A couple of random thoughts, maybe over Shabbat I’ll find a way to link them together:

As I mentioned, I’m in Toronto right now, and on Shabbat we’re planning on walking up to Ayin Letzion, which is a minyan that I was involved with while we were on shlichut here. It is possible that the Rabbi there will ask me to say a few words at Sudat Shlishit, it’s also not impossible that I’ll have the opportunity to say something at the Shabbat table, so I’d better come up with a few coherent thoughts, just in case.

Parshat Va’etchanan is jam-packed with concepts, both big and small. It’s almost like a “Greatest hits” parsha - 10 commandments and Shema Yisrael are two biggies that spring to mind, but there are plenty of other meaningful goodies.

A couple of random thoughts, maybe over Shabbat I’ll find a way to link them together:

- The Parsha opens with Moshe’s “Plea” (Chanan) to HaShem, asking for permission to enter Eretz Yisrael.

Rashi has a lot of trouble with this word, “Chinun”; he claims that it is a type of prayer – specifically a “free gift”.

Look carefully at that Rashi, and the Ikar Siftei Chachamim, I think that he is trying to hell us something about that nature of prayer – that it shouldn’t be a deal: “Please give me x because I did y” or more commonly “If you give me x, I’ll do y”, rather even if we believe that we have ‘Ma’asim Tovim”, we shouldn’t use them as a basis for a heartfelt request. - Moshe’s particular request always gives me Goosebumps – he asks HaShem for permission to enter Eretz Yisrael – this was his deepest and most heartfelt request, and one that was denied.

- I get Goosebumps because that which was denied to Moshe Rabeinu was given to our generation. How is it that when I get up in the morning and walk to shul, I am able to fulfill a Mitzvah that was denied to Moshe, the mitzvah of walking 4 amot in Eretz Yisrael.

Other thoughts about the parsha:

- Moshe’s response to the denial of his Tfilla, he accepts the judgment without anger or complaint.

- Why does he warn us against worship of Ba’al Pe’or, a disgusting type of idol worship that involves defecating in front of an idol – I think that there is definitely a message there for our generation which often sees a total disregard for common respect or appropriate action

- Why does Moshe designate three cities of refuge? He knows that these cities will not function for many years until after the Western side bank of the Jordan (“West bank”?) has been conquered and settled.

- Before repeating the 10 commandments, Moshe reminds us that we all heard them directly from HaShem – there is definitely a strong message in there.

There are many other goodies in this week’s Parsha, looks like this blogging thing is a great way to get me to think :)

Shabbat Shalom

Labels:

Parsha

Thursday, July 26, 2007

What's with that Title?

I'm going to try to blog at least a few lines every day, hopefully soon I'll settle into a style that works for me.

Why did I call this blog 'Between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv?"

I live in Modi'in, which geographically is almost mid-point between Israel's two major cities, but one of the reasons that we choose to live in Modi'in is that it is between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv in other ways as well.

Population-wise, Modi'in is a mixture of people who came from Jerusalem (or at least a "Jerusalem mentality") and Tel Aviv (or a "Tel Aviv Mentality").

Jerusalem is the spiritual centre of the Universe. Most of the people there strive to keep Mitzvot and get closer to G-d. Tel Aviv is the industrial centre of Israel. Many of the people there are more concerned with the mundane, sometimes at the expense of their spiritual needs.

It's now a few days after Tisha B'Av. A few years ago one of the major Israeli dailies summed up the difference between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv with two photos, showing a typical Tisha B'Av in each city. The Jerusalem photo showed the Kotel, packed with people crying for a loss almost 2000 years ago. The Tel Aviv photo showed a restaurant packed with people, unaware that they had lost anything at all.

Unfortunately, today Jerusalem and Tel Aviv represent two separate worlds: The world of people who cry on Tisha B'Av, and the world of people who aren't aware that there is anything to cry about.

The real reason to cry today is that these two worlds aren't capable of understanding, or even talking to each other.

Recently I attended a dinner to honour Rabbi Brovender. One of the things he recounted, sadly was how much Israeli society has become self-segregated. He said that when he lived in Kiryat Moshe (Jerusalem) in the 1960s, you would see people on the street with hats and jackets, knitted kippot, shorts and ponytails, or any other style of dress. Unfortunately, today people tend to live in neighbourhoods where everyone dresses (and thinks) alike.

As I said, Modi'in is one of the few places in Israel where the demographics represent "Amcha" - Israeli society as a whole.

We are in the process of moving into a new house, and are starting to meet our new neighbours. Some where kipot, others don't, but hopefully we will all live together on the same project any be able to not just see each other, but learn and benefit from each other.

In my humble opinion, this should be the future of Israel - not a wall between us and the Palestinians, but a bridge between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

Why did I call this blog 'Between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv?"

I live in Modi'in, which geographically is almost mid-point between Israel's two major cities, but one of the reasons that we choose to live in Modi'in is that it is between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv in other ways as well.

Population-wise, Modi'in is a mixture of people who came from Jerusalem (or at least a "Jerusalem mentality") and Tel Aviv (or a "Tel Aviv Mentality").

Jerusalem is the spiritual centre of the Universe. Most of the people there strive to keep Mitzvot and get closer to G-d. Tel Aviv is the industrial centre of Israel. Many of the people there are more concerned with the mundane, sometimes at the expense of their spiritual needs.

It's now a few days after Tisha B'Av. A few years ago one of the major Israeli dailies summed up the difference between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv with two photos, showing a typical Tisha B'Av in each city. The Jerusalem photo showed the Kotel, packed with people crying for a loss almost 2000 years ago. The Tel Aviv photo showed a restaurant packed with people, unaware that they had lost anything at all.

Unfortunately, today Jerusalem and Tel Aviv represent two separate worlds: The world of people who cry on Tisha B'Av, and the world of people who aren't aware that there is anything to cry about.

The real reason to cry today is that these two worlds aren't capable of understanding, or even talking to each other.

Recently I attended a dinner to honour Rabbi Brovender. One of the things he recounted, sadly was how much Israeli society has become self-segregated. He said that when he lived in Kiryat Moshe (Jerusalem) in the 1960s, you would see people on the street with hats and jackets, knitted kippot, shorts and ponytails, or any other style of dress. Unfortunately, today people tend to live in neighbourhoods where everyone dresses (and thinks) alike.

As I said, Modi'in is one of the few places in Israel where the demographics represent "Amcha" - Israeli society as a whole.

We are in the process of moving into a new house, and are starting to meet our new neighbours. Some where kipot, others don't, but hopefully we will all live together on the same project any be able to not just see each other, but learn and benefit from each other.

In my humble opinion, this should be the future of Israel - not a wall between us and the Palestinians, but a bridge between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

Welcome to my blog...

Well, this is my blog.

I'm not sure what type of blog this will turn into, or whether I'll even manage to blog regularly, but there are times that I have thoughts that I'd like to write down, and who knows, maybe someday someone will want to read them.

In case you've stumbled on this blog by accident and are wondering who I am, well a bit about me -

My name is Michael. I was born in Wellington, New Zealand, but currently live in Modi'in Israel. I am married with four kids (bli Ayin Hara).

I'm a technical writer and am currently contracting long-term for a company in Toronto, Canada.

Well, now that I've have something in my first post, I guess that I can get back to work. If you do stumble upon my humble blog, please leave a comment just so I know that someone is out there.

I'm not sure what type of blog this will turn into, or whether I'll even manage to blog regularly, but there are times that I have thoughts that I'd like to write down, and who knows, maybe someday someone will want to read them.

In case you've stumbled on this blog by accident and are wondering who I am, well a bit about me -

My name is Michael. I was born in Wellington, New Zealand, but currently live in Modi'in Israel. I am married with four kids (bli Ayin Hara).

I'm a technical writer and am currently contracting long-term for a company in Toronto, Canada.

Well, now that I've have something in my first post, I guess that I can get back to work. If you do stumble upon my humble blog, please leave a comment just so I know that someone is out there.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)